There are three conditions that must be present for a situation to

be considered an ethical dilemma. The first condition occurs in

situations when an individual, called the “agent,” must make a decision

about which course of action is best. Situations that are uncomfortable

but that don’t require a choice, are not ethical dilemmas. For example,

students in their internships are required to be under the supervision

of an appropriately credentialed social work field instructor.

Therefore, because there is no choice in the matter, there is no ethical

violation or breach of confidentiality when a student discusses a case

with the supervisor. The second condition for ethical dilemma is that

there must be different courses of action to choose from. Third, in an

ethical dilemma, no matter what course of action is taken, some ethical

principle is compromised. In other words, there is no perfect solution.

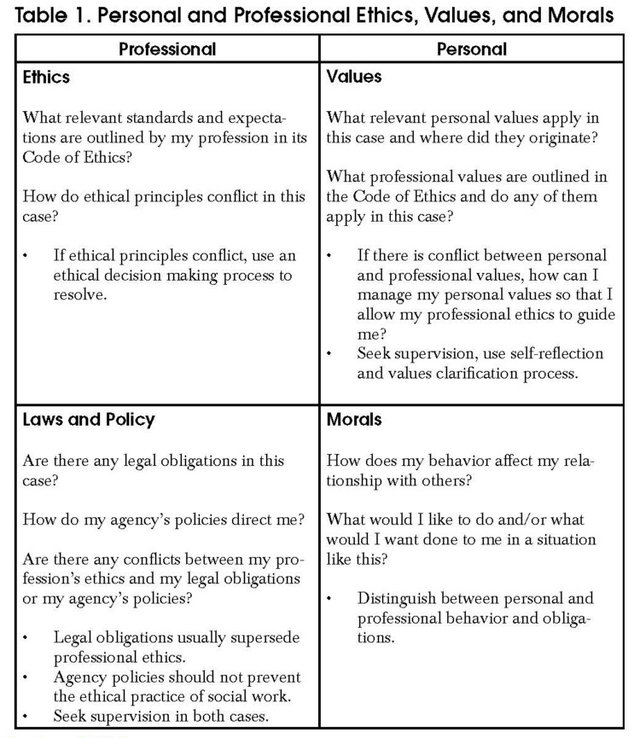

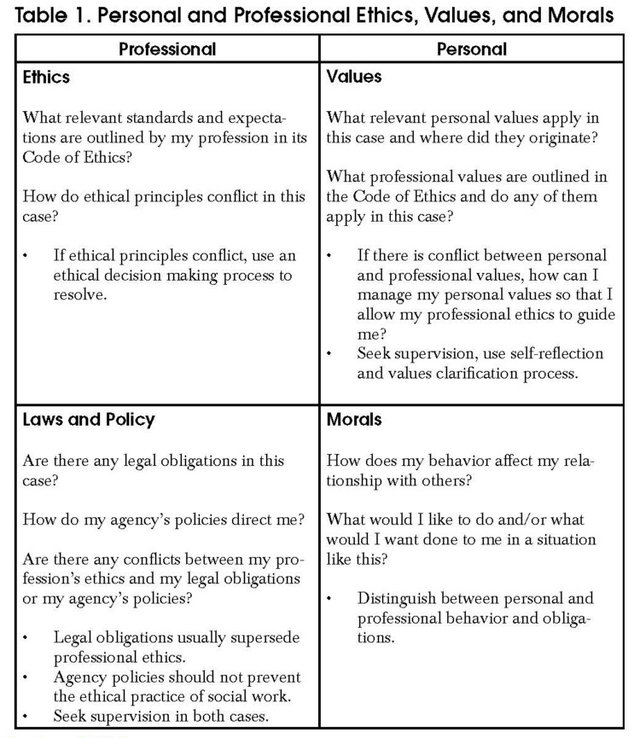

In determining what constitutes an ethical dilemma, it is necessary to make a distinction between ethics, values, morals, and laws and policies. Ethics are prepositional statements (standards) that are used by members of a profession or group to determine what the right course of action in a situation is. Ethics rely on logical and rational criteria to reach a decision, an essentially cognitive process (Congress, 1999; Dolgoff, Loewenberg, & Harrington, 2009; Reamer, 1995; Robison & Reeser, 2002). Values, on the other hand, describe ideas that we value or prize. To value something means that we hold it dear and feel it has worth to us. As such, there is often a feeling or affective component associated with values (Allen & Friedman, 2010). Often, values are ideas that we aspire to achieve, like equality and social justice. Morals describe a behavioral code of conduct to which an individual ascribes. They are used to negotiate, support, and strengthen our relationships with others (Dolgoff, Loewenberg, & Harrington, 2009).

Finally, laws and agency policies are often involved in complex cases, and social workers are often legally obligated to take a particular course of action. Standard 1.07j of the Code of Ethics (NASW, 1996) recognizes that legal obligations may require social workers to share confidential information (such as in cases of reporting child abuse) but requires that we protect confidentiality to the “extent permitted by law.” Although our profession ultimately recognizes the rule of law, we are also obligated to work to change unfair and discriminatory laws. There is considerably less recognition of the supremacy of agency policy in the Code, and Ethical Standard 3.09d states that we must not allow agency policies to interfere with our ethical practice of social work.

It is also essential that the distinction be made between personal and professional ethics and values (Congress, 1999; Wilshere, 1997). Conflicts between personal and professional values should not be considered ethical dilemmas for a number of reasons. Because values involve feelings and are personal, the rational process used for resolving ethical dilemmas cannot be applied to values conflicts. Further, when an individual elects to become a member of a profession, he or she is agreeing to comply with the standards of the profession, including its Code of Ethics and values. Recent court cases have supported a profession’s right to expect its members to adhere to professional values and ethics. (See, for example, the Jennifer Keeton case at Augusta State University and the Julea Ward case at Eastern Michigan University.) The Council on Social Work Education states that students should “recognize and manage personal values in a way that allows professional values to guide practice” (EPAS 1.1). Therefore, although they can be difficult and uncomfortable, conflicts involving personal values should not be considered ethical dilemmas.

Two Types of Dilemmas

An “absolute” or “pure” ethical dilemma only occurs when two (or more) ethical standards apply to a situation but are in conflict with each other. For example, a social worker in a rural community with limited mental health care services is consulted on a client with agoraphobia, an anxiety disorder involving a fear of open and public spaces. Although this problem is outside of the clinician’s general competence, the limited options for treatment, coupled with the client`s discomfort in being too far from home, would likely mean the client might not receive any services if the clinician declined on the basis of a lack of competence (Ethical Standard 1.04). Denying to see the patient then would be potentially in conflict with our commitment to promote the well-being of clients (Ethical Standard 1.01). This is a pure ethical dilemma because two ethical standards conflict. It can be resolved by looking at Ethical Standard 4.01, which states that social workers should only accept employment (or in this case, a client) on the basis of existing competence or with “the intention to acquire the necessary competence.” The social worker can accept the case, discussing the present limits of her expertise with the client and following through on her obligation to seek training or supervision in this area.

However, there are some complicated situations that require a decision but may also involve conflicts between values, laws, and policies. Although these are not absolute ethical dilemmas, we can think of them as “approximate” dilemmas. For example, an approximate dilemma occurs when a social worker is legally obligated to make a report of child or domestic abuse and has concerns about the releasing of information. The social worker may experience tension between the legal requirement to report and the desire to respect confidentiality. However, because the NASW Code of Ethics acknowledges our obligation to follow legal requirements and to intervene to protect the vulnerable, technically, there is no absolute ethical dilemma present. However, the social worker experiences this as a dilemma of some kind and needs to reach some kind of resolution. Breaking the situation down and identifying the ethics, morals, values, legal issues, and policies involved as well as distinguishing between personal and professional dimensions can help with the decision-making process in approximate dilemmas. Table 1 (at beginning of this article) is an illustration of how these factors might be considered.

Conclusion

When writing an ethical dilemma paper or when attempting to resolve an ethical dilemma in practice, social workers should determine if it is an absolute or approximate dilemma; distinguish between personal and professional dimensions; and identify the ethical, moral, legal, and values considerations in the situation. After conducting this preliminary analysis, an ethical decision-making model can then be appropriately applied.

In determining what constitutes an ethical dilemma, it is necessary to make a distinction between ethics, values, morals, and laws and policies. Ethics are prepositional statements (standards) that are used by members of a profession or group to determine what the right course of action in a situation is. Ethics rely on logical and rational criteria to reach a decision, an essentially cognitive process (Congress, 1999; Dolgoff, Loewenberg, & Harrington, 2009; Reamer, 1995; Robison & Reeser, 2002). Values, on the other hand, describe ideas that we value or prize. To value something means that we hold it dear and feel it has worth to us. As such, there is often a feeling or affective component associated with values (Allen & Friedman, 2010). Often, values are ideas that we aspire to achieve, like equality and social justice. Morals describe a behavioral code of conduct to which an individual ascribes. They are used to negotiate, support, and strengthen our relationships with others (Dolgoff, Loewenberg, & Harrington, 2009).

Finally, laws and agency policies are often involved in complex cases, and social workers are often legally obligated to take a particular course of action. Standard 1.07j of the Code of Ethics (NASW, 1996) recognizes that legal obligations may require social workers to share confidential information (such as in cases of reporting child abuse) but requires that we protect confidentiality to the “extent permitted by law.” Although our profession ultimately recognizes the rule of law, we are also obligated to work to change unfair and discriminatory laws. There is considerably less recognition of the supremacy of agency policy in the Code, and Ethical Standard 3.09d states that we must not allow agency policies to interfere with our ethical practice of social work.

It is also essential that the distinction be made between personal and professional ethics and values (Congress, 1999; Wilshere, 1997). Conflicts between personal and professional values should not be considered ethical dilemmas for a number of reasons. Because values involve feelings and are personal, the rational process used for resolving ethical dilemmas cannot be applied to values conflicts. Further, when an individual elects to become a member of a profession, he or she is agreeing to comply with the standards of the profession, including its Code of Ethics and values. Recent court cases have supported a profession’s right to expect its members to adhere to professional values and ethics. (See, for example, the Jennifer Keeton case at Augusta State University and the Julea Ward case at Eastern Michigan University.) The Council on Social Work Education states that students should “recognize and manage personal values in a way that allows professional values to guide practice” (EPAS 1.1). Therefore, although they can be difficult and uncomfortable, conflicts involving personal values should not be considered ethical dilemmas.

Two Types of Dilemmas

An “absolute” or “pure” ethical dilemma only occurs when two (or more) ethical standards apply to a situation but are in conflict with each other. For example, a social worker in a rural community with limited mental health care services is consulted on a client with agoraphobia, an anxiety disorder involving a fear of open and public spaces. Although this problem is outside of the clinician’s general competence, the limited options for treatment, coupled with the client`s discomfort in being too far from home, would likely mean the client might not receive any services if the clinician declined on the basis of a lack of competence (Ethical Standard 1.04). Denying to see the patient then would be potentially in conflict with our commitment to promote the well-being of clients (Ethical Standard 1.01). This is a pure ethical dilemma because two ethical standards conflict. It can be resolved by looking at Ethical Standard 4.01, which states that social workers should only accept employment (or in this case, a client) on the basis of existing competence or with “the intention to acquire the necessary competence.” The social worker can accept the case, discussing the present limits of her expertise with the client and following through on her obligation to seek training or supervision in this area.

However, there are some complicated situations that require a decision but may also involve conflicts between values, laws, and policies. Although these are not absolute ethical dilemmas, we can think of them as “approximate” dilemmas. For example, an approximate dilemma occurs when a social worker is legally obligated to make a report of child or domestic abuse and has concerns about the releasing of information. The social worker may experience tension between the legal requirement to report and the desire to respect confidentiality. However, because the NASW Code of Ethics acknowledges our obligation to follow legal requirements and to intervene to protect the vulnerable, technically, there is no absolute ethical dilemma present. However, the social worker experiences this as a dilemma of some kind and needs to reach some kind of resolution. Breaking the situation down and identifying the ethics, morals, values, legal issues, and policies involved as well as distinguishing between personal and professional dimensions can help with the decision-making process in approximate dilemmas. Table 1 (at beginning of this article) is an illustration of how these factors might be considered.

Conclusion

When writing an ethical dilemma paper or when attempting to resolve an ethical dilemma in practice, social workers should determine if it is an absolute or approximate dilemma; distinguish between personal and professional dimensions; and identify the ethical, moral, legal, and values considerations in the situation. After conducting this preliminary analysis, an ethical decision-making model can then be appropriately applied.

How to Resolve Ethical Dilemmas in the Workplace

Employees make decisions at all levels of a company, whether at the top, on the front line or anywhere in between. Every employee in an organization is exposed to the risk of facing an ethical dilemma at some point, and some ethical decisions can be more challenging to fully understand than others. Knowing how to resolve ethical dilemmas in the workplace can increase your decision-making effectiveness while keeping you and your company on the right side of the law and public sentiment.

1.

Consult your company's code of ethics for formal guidance. This simple

act may be able to resolve your dilemma immediately, depending on how

comprehensive and specific your company's ethics statement is. Your code

of ethics can provide a backdrop on which to weigh the pros and cons of

business decisions, giving you a clearer picture of which decision is

more in line with the company's ethical commitments.

2.

Share your dilemma with your supervisor to take advantage of her

experience. Front-line employees can face a number of ethical dilemmas

in their jobs, such as deciding whether to give out a refund that does

not specifically adhere to company policies or whether to report

suspicions of internal theft which cannot be proven. Taking ethical

questions to supervisors can keep employees out of trouble in addition

to resolving conflicts.

3.

Discuss your dilemma with other executives if you are at the top of

your organization. Executives and company owners make some of the

farthest-reaching decisions in any organization, adding weight and

additional challenges to ethical dilemmas. As an executive, it is

important to show your competence at solving problems on your own, but

there is nothing wrong with asking for help from time to time. Other

executive team members should appreciate your commitment to making the

right decision and should be able to provide unique insights into your

problem.

4.

Speak with peers and colleagues from other companies if you can do so

without divulging company secrets. If you are a sole proprietor, you may

not have any other top-level managers to consult with. Seek out someone

you trust from a business networking group, a previous employer or your

college years to gain insight from others. Consider speaking with

friends from diverse cultural backgrounds to gain an even wider range of

insights.

5.

Read past news articles about other companies faced with your specific

dilemma. Determine how others have dealt with your challenge before and

take note of the outcome of their decisions. News outlets like to cover

certain large company decisions, such as laying off workers, endorsing

political candidates and bending accounting rules, which can have

ethical impacts in society. Reading what happened to others after making

their decisions can give you a glimpse into what to expect if you make a

similar decision.

This is the first of a two-part series on ethical conflicts in the workplace. The next blog deals with employee-generated actions that can have legal consequences. Today I deal with discriminatory actions by one’s employer that go unresolved.

Have you been sexually harassed by a co-worker or your supervisor? Are you a victim of gender discrimination? Have you been cyber-bullied in the workplace? These are three of the most troubling issues that cause distress for an employee and create ethical dilemmas in the workplace. I have previously blogged about these issues and provide links to them below for more comprehensive coverage. My goal today is to provide advice on how to spot discrimination and what to do about it.

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination. The legal definition of sexual harassment is “unwelcome verbal, visual, or physical conduct of a sexual nature that is severe or pervasive and affects working conditions or creates a hostile work environment.”

A hostile work environment is defined as: sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature, when such advances, requests, or conduct have the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual's work performance by creating an intimidating, hostile, humiliating, or sexually offensive work environment.

To show a hostile work environment, an employee must prove the following.

Let’s assume your boss threatens to stifle your career advancement unless you sleep with him. This is unlawful whether you submit and avoid the threatened harm or resist and suffer the consequences. Your first step should be to make it clear to your boss this is an unwelcomed advance. If the offensive behavior persists, you should report it to the HR Department where Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) matters are dealt with. You can also file a complaint with the EEOC and/or your state’s fair employment agency.

Gender Discrimination

Gender bias is wrong in any form whether based on age, sex, or sexual orientation. The law has not caught up with the rights of transgender individuals but the spirit of the law should protect trans people in the workplace. The workplace should be a welcoming environment and the culture one of inclusion.

Gender identity issues have surfaced recently because of the landmark opinion by the U.S. Supreme Court on June 26, 2015, that established same-sex couples can marry nationwide. It’s not a leap to focus attention on the rights of the LGBT community. The basic ethical principal here is one of fair treatment. Each of us deserves respect for who we are. Discriminating against anyone based on gender identity is wrong. After all, what does this have to do with workplace performance?

Gender identity discrimination can include terminating a transgender employee after the employer finds out about the employee's gender identity or planned transition; denying a transgender employee access to workplace restroom facilities available to other employees; harassing a transgender employee; permitting and/or refusing to investigate claims of harassment by coworkers and supervisors; or any other negative employment action taken because of an employee's gender identity.

Discrimination based on gender identity is not specifically prohibited under federal law but there are legislative efforts to pass federal laws to make it explicitly illegal. There is also some case law interpreting sex discrimination laws to encompass gender identity in certain circumstances. Protection from gender identity discrimination is enforced by state or local anti-discrimination agencies in 18 states.

Given the relative newness of gender identity issues, I suggest you first contact The Human Rights Campaign for advice and emotional support. HRC works to achieve equality for the LGBT community and represents a force of more than 1.5 million members and supporters nationwide.

Cyber-bullying

Workplace Bullying refers to repeated, unreasonable actions of individuals (or a group) directed towards an employee (or a group of employees), which are intended to intimidate, degrade, humiliate, or undermine, or which create a risk to the health or safety of the employee(s) including physical and emotional stress.

Workplace Bullying often involves an abuse or misuse of power. Bullying behavior creates feelings of defenselessness and injustice in the target and undermines an individual’s right to dignity at work. Bullying is different from aggression. Whereas aggression may involve a single act, bullying involves repeated attacks against the target, creating an on-going pattern of behavior. “Tough” or “demanding” bosses are not necessarily bullies so long as they are respectful and fair and their primary motivation is to obtain the best performance by setting high yet reasonable expectations for working safely.

Cyber Bullying in the Workplace usually looks like offensive emails or text messages containing jokes or inappropriate wording towards a specific race, nationality, or about sexual preference. In these cases, the words uttered have a direct effect on the target of the bullying act through threatening email being sent to the target anonymously or not. It might include a response that is copied and pasted for the whole office to see.

Sharing embarrassing situations relating to the target with everyone online, being offensive and mean to the target on various social media websites and networks, spreading rumors or gossip online which could have a serious effect on a fellow co-worker, and downright mean-spirited actions are meant to harm the target whether on a personal or professionals level.

Cyber bullying can cause significant emotional distress and significantly lead to diminished workplace performance. The danger of cyber bullying in the workplace is that it follows you home after working hours. The target is put under constant harassment even when the working hours are over. The only way to avoid such harassment is having it reported to try and put an end to it.

Cyber bullying in the workplace needs to be addressed through promoting a work environment that refuses to nurture a bully. As with most actions in the workplace, the best way to prevent cyber bullying is to create an ethical culture in the organization. Top management must make it clear that any form of bullying will not be tolerated.

Ethical Dilemmas in the Workplace for Employees

How to Spot Abusive Behavior and What to Do About itThis is the first of a two-part series on ethical conflicts in the workplace. The next blog deals with employee-generated actions that can have legal consequences. Today I deal with discriminatory actions by one’s employer that go unresolved.

Have you been sexually harassed by a co-worker or your supervisor? Are you a victim of gender discrimination? Have you been cyber-bullied in the workplace? These are three of the most troubling issues that cause distress for an employee and create ethical dilemmas in the workplace. I have previously blogged about these issues and provide links to them below for more comprehensive coverage. My goal today is to provide advice on how to spot discrimination and what to do about it.

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination. The legal definition of sexual harassment is “unwelcome verbal, visual, or physical conduct of a sexual nature that is severe or pervasive and affects working conditions or creates a hostile work environment.”

A hostile work environment is defined as: sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature, when such advances, requests, or conduct have the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual's work performance by creating an intimidating, hostile, humiliating, or sexually offensive work environment.

To show a hostile work environment, an employee must prove the following.

- He/she was subjected to conduct of a sexual nature (e.g., inappropriate touching, sexual epithets, jokes, gossip, sexual comments, requests for sex, sexually suggestive pictures and objects, leering, whistling, sexual gestures).

- The conduct was unwelcome.

- The conduct had the purpose or effect of creating an intimidating, hostile, humiliating, or sexually offensive work environment.

- The conduct unreasonably interfered with the employee's work performance or altered the terms and conditions of employment.

Let’s assume your boss threatens to stifle your career advancement unless you sleep with him. This is unlawful whether you submit and avoid the threatened harm or resist and suffer the consequences. Your first step should be to make it clear to your boss this is an unwelcomed advance. If the offensive behavior persists, you should report it to the HR Department where Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) matters are dealt with. You can also file a complaint with the EEOC and/or your state’s fair employment agency.

Gender Discrimination

Gender bias is wrong in any form whether based on age, sex, or sexual orientation. The law has not caught up with the rights of transgender individuals but the spirit of the law should protect trans people in the workplace. The workplace should be a welcoming environment and the culture one of inclusion.

Gender identity issues have surfaced recently because of the landmark opinion by the U.S. Supreme Court on June 26, 2015, that established same-sex couples can marry nationwide. It’s not a leap to focus attention on the rights of the LGBT community. The basic ethical principal here is one of fair treatment. Each of us deserves respect for who we are. Discriminating against anyone based on gender identity is wrong. After all, what does this have to do with workplace performance?

Gender identity discrimination can include terminating a transgender employee after the employer finds out about the employee's gender identity or planned transition; denying a transgender employee access to workplace restroom facilities available to other employees; harassing a transgender employee; permitting and/or refusing to investigate claims of harassment by coworkers and supervisors; or any other negative employment action taken because of an employee's gender identity.

Discrimination based on gender identity is not specifically prohibited under federal law but there are legislative efforts to pass federal laws to make it explicitly illegal. There is also some case law interpreting sex discrimination laws to encompass gender identity in certain circumstances. Protection from gender identity discrimination is enforced by state or local anti-discrimination agencies in 18 states.

Given the relative newness of gender identity issues, I suggest you first contact The Human Rights Campaign for advice and emotional support. HRC works to achieve equality for the LGBT community and represents a force of more than 1.5 million members and supporters nationwide.

Cyber-bullying

Workplace Bullying refers to repeated, unreasonable actions of individuals (or a group) directed towards an employee (or a group of employees), which are intended to intimidate, degrade, humiliate, or undermine, or which create a risk to the health or safety of the employee(s) including physical and emotional stress.

Workplace Bullying often involves an abuse or misuse of power. Bullying behavior creates feelings of defenselessness and injustice in the target and undermines an individual’s right to dignity at work. Bullying is different from aggression. Whereas aggression may involve a single act, bullying involves repeated attacks against the target, creating an on-going pattern of behavior. “Tough” or “demanding” bosses are not necessarily bullies so long as they are respectful and fair and their primary motivation is to obtain the best performance by setting high yet reasonable expectations for working safely.

Cyber Bullying in the Workplace usually looks like offensive emails or text messages containing jokes or inappropriate wording towards a specific race, nationality, or about sexual preference. In these cases, the words uttered have a direct effect on the target of the bullying act through threatening email being sent to the target anonymously or not. It might include a response that is copied and pasted for the whole office to see.

Sharing embarrassing situations relating to the target with everyone online, being offensive and mean to the target on various social media websites and networks, spreading rumors or gossip online which could have a serious effect on a fellow co-worker, and downright mean-spirited actions are meant to harm the target whether on a personal or professionals level.

Cyber bullying can cause significant emotional distress and significantly lead to diminished workplace performance. The danger of cyber bullying in the workplace is that it follows you home after working hours. The target is put under constant harassment even when the working hours are over. The only way to avoid such harassment is having it reported to try and put an end to it.

Cyber bullying in the workplace needs to be addressed through promoting a work environment that refuses to nurture a bully. As with most actions in the workplace, the best way to prevent cyber bullying is to create an ethical culture in the organization. Top management must make it clear that any form of bullying will not be tolerated.

Great Article

ReplyDeleteCyber Security Projects

projects for cse

JavaScript Training in Chennai

JavaScript Training in Chennai